lntroduction

The stagnation of delivery during the birth of the shoulders after the head has been born, is referred to as shoulder dystocia. It does not refer to the slightly difficult progression of the anterior shoulder in the case of a folded arm or if the expulsive force subsides. True shoulder dystocia necessitates additional measures without which the birth will not proceed further. This is a serious complication which requires immediate expert intervention. The problem occurs in 0.2% to 0.6% of births. In some cases, timely anticipation can prevent shoulder dystocia.

For a good understanding of the measures to prevent shoulder dystocia and for an insight into the management of this complication, some knowledge of the aetiology is indispensable.

Theoretical Background To Shoulder Dystocia

Physiology

Under physiological circumstances, the shoulders will pass obliquely through the pelvic brim. First, the posterior shoulder and subsequently the anterior shoulder. The engagement (passage through the pelvic brim) of the anterior shoulder takes place ‘automatically’ during the birth of the head (the flexion phase). As the posterior shoulder descends into the sacral hollow, the anterior shoulder can rotate left or right under the pubic symphysis. The anterior shoulder then passes through the pelvic brim and pelvic outlet and is born. As soon as the anterior shoulder has passed under the pubic symphysis, space is created for the posterior shoulder to glide more deeply into the sacral hollow and be born.

Pathology

During the engagement of the shoulders, it is possible for something to go wrong due to the width of the shoulders, the dimensions or the shape of the pelvis, the relationship of the shoulders with respect to the pelvis or the policy of the care provider. If the shoulders engage in the anteroposterior orientation instead of in the oblique position, or if they both pass through the pelvic brim at the same time, the anterior shoulder will remain stuck behind the pubic symphysis and the posterior shoulder will remain impinged behind the sacral promontory. Typical for this ‘high’ or ’posterior’ shoulder dystocia is that the head will not be born completely and will appear to be drawn back into the birth canal (‘turtle sign’). The chin will appear to be stuck against the perineum and external rotation does not occur.

It can also be the case that the shoulders engage transversely and remain in the transverse orientation relative to the pelvic floor. In this transverse shoulder dystocia, the external rotation does not occur either but the head is clearly born. ‘Anterior’ shoulder dystocia is, however, the most common form. In this case, the posterior shoulder has descended into the pelvis but the anterior shoulder remains stuck in the pelvic brim against the pubic symphysis. The management of this type of shoulder dystocia will be discussed in greater detail.

Aetiology Of Shoulder Dystocia

In the aetiology of shoulder dystocia, a distinction is made between causes due to the foetus, the pelvis and the obstetric management. In practice, this distinction is less absolute. For example, a larger-than-normal child will be relatively too large for the pelvis concerned, while some pelvic and shoulder dimensions will lead to shoulder dystocia when one type of obstetric management is applied, yet will not occur during application of another management procedure.

The Foetus

In a full-term foetus, the circumference of the shoulders exceeds that of the head. This does not usually form a problem for parturition due to the considerable mobility and deformability of the shoulders in the anteroposterior and cranial-caudal directions. However, the greater the degree to which the shoulder circumference exceeds that of the head, the greater the risk of shoulder dystocia. Although the increase in the biparietal distance is smaller during the third trimester of pregnancy than during earlier stages, the biacromial diameter increases at a constant rate. Post-term pregnancy is therefore associated with a less favourable skull/shoulder ratio. Gestational diabetes also causes a less favourable ratio, as brain tissue is not sensitive to hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinaemia, whereas the shoulders do exhibit extra growth as a consequence of these phenomena. Furthermore, if the skull is only born after considerable moulding, as is the case with prolonged dilation and delivery, it can result in an unfavourable skull/shoulder ratio.

The Pelvis

For a normally proportioned child, once the head has passed through the pelvis the shoulders will generally be able to follow. However, in the case of pelvic abnormalities this might not be the case. A pelvis that is generally narrow right along its length can eventually allow the head to pass through after a prolonged moulding but stagnation of the shoulders may follow. Other pelvic anomalies, for example a flat narrow pelvis, can form a specific hindrance for the shoulders. This complication can sometimes be avoided by adjusting the management. This underlines the importance of assessing the maternal pelvis during pregnancy, in order to be prepared possible complications.

Management

The prevention of shoulder dystocia starts with the timely recognition of an increased risk.

Predisposing factors for the development of shoulder dystocia are:

- History of shoulder dystocia.

- Macrosomia.

- Macrosomia in the history.

- Multiparity.

- Diabetes mellitus.

- Obesity.

- Post-term pregnancy.

- Prolonged dilation/delivery.

- Pelvic anomaly.

- Assisted delivery.

If predisposing factors are not taken into account, a practitioner is more likely to be caught unaware by a shoulder dystocia and not be able to respond adequately. Adjustment of the management includes, ensuring an empty bladder during the delivery, maximum flexion at the hips and an arrangement with extra space for the birth of the shoulders (patient’s legs in leg rests or foot stirrups with buttocks on the edge of the table, or on inverted placenta pan or bedpan under the buttocks).

An episiotomy is recommended as this gives better access to the child. Extension of the episiotomy or a double episiotomy is not indicated if shoulder dystocia arises since this is a skeletal problem and not a soft tissue dystocia.

A frequently-made management error is forcing the external rotation before the head has been adequately born. The shoulders are then hindered in spontaneously adopting the diagonal position necessary for a problem-free engagement. Consequently, after the posterior shoulder has engaged, it can end up tightly behind the pubic symphysis again. Another regularly occurring error is allowing the woman to push strongly or even applying fundal pressure, if the anterior shoulder is still directly behind the pubic symphysis after the birth of the head. The chance of spontaneous rotation is then lost and the added pressure hinders the internal rotation of the shoulders even more.

Consequences Of Shoulder Dystocia

Shoulder dystocia sometimes leads to the death of the foetus and is associated with a high perinatal and maternal morbidity. The morbidity of the mother usually concerns damage to the soft birth canal or the uterus, sometimes associated with severe blood loss. Symphysiolysis has also been noted as a complication. For the foetus, asphyxia is a direct consequence. Additionally, the various attempts to alleviate the shoulder dystocia can bring about specific injuries to the foetus and mother. The most frequently occurring foetal injuries are clavicular fractures (sometimes with lung and vascular injuries), humerus fractures, and neurological damage to the brachial plexus. The most frequent is Erb’s palsy (5th-6th cervical nerve root). Extensive plexus lesions also occur, such as damage to the higher cervical nerve roots (3rd-4th) with diaphragm paralysis and Horner’s syndrome as a consequence. Klumpke’s palsy occurs after damage to the 8th cervical nerve root and 1st thoracic nerve root. These injuries cannot always be prevented. However, the severity can be reduced by taking well-considered, targeted and careful steps.

Prevention Of Complications

Fundal pressure and traction when applied without good reason or even counterproductively, has already been discussed as a factor that may lead to lead to or exacerbate complications. Also, hasty and rough actions due to concerns about losing the child can have a morbidity-enhancing effect. Finally it needs to be realised that if the child becomes asphyctic, hypotonia of the musculoskeletal system will occur. Due to this hypotonia, traction of the head will easily result in neurological damage to the cervical plexus.

After the birth, the newborn and the birth canal need to be carefully examined. Haematomas in the genital tract may only manifest several hours after the birth. After intensive vaginal manipulations, the possibility of urinary retention must be considered. This needs to be checked as failure to recognise this in time can lead to severe neurogenic bladder damage.

Correction Of Shoulder Dystocia

Procedure

- Place an inverted kidney bowl or bedpan under the woman’s buttocks (provides more space for manoeuvring the head downwards) or place the woman’s legs in leg rests or foot stirrups with her buttocks on the edge of the bed.

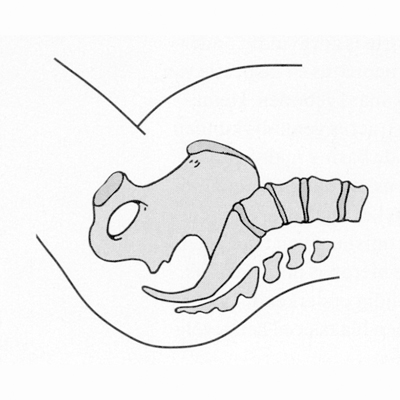

- Place the woman in the McRoberts position by bringing the legs into maximum flexion at the hip (usually the standard position during active pushing). Although this leads to a decrease in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic brim, the pelvic inclination (angle between the pelvic brim and the anteroposterior axis) becomes smaller. Lumbar lordosis is attenuated and the pubic symphysis is pulled over the anterior shoulder, so that the anterior shoulder can pass through the pelvic brim. Moreover, this position results in a widening of the pelvic outlet [Figures 40, 41]. As a result, it will be easier for the anterior shoulder to rotate out from under the pubic symphysis.

Figure 40

Figure 40

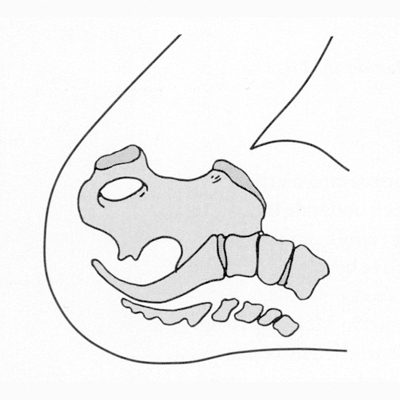

Figure 41

Figure 41

- Take hold of the head in a biparietal manner. Under no circumstances may the external rotation be forced using the head. Doing this could reinforce the tendency of the shoulders to remain in the anteroposterior position. If necessary, reverse the external rotation.

- While the woman is not pushing, the head should be pushed upwards slightly and moved dorsally in the direction of the rectum in order to release the anterior shoulder from the pubic symphysis (Hibbard’s method).

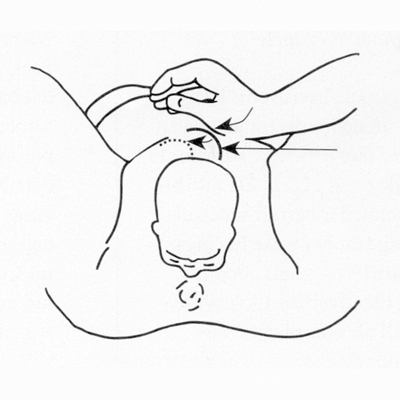

- Attempt to bring the shoulders of the foetus into a diagonal position by exerting downward, lateral suprapubic pressure [Figure 42]. This suprapubic diagonal pressure can enhance the turning moment of the anterior shoulder. The woman may not push during this movement and, in particular, no fundal pressure may be applied as this could result in the shoulders being permanently pushed into the unwanted position.

Figure 42

Figure 42

- Move the head sacrally, when suprapubic pressure is applied. After the anterior shoulder has been pushed diagonally into the pelvic brim by suprapubic pressure, the head should be further flexed sacrally and if necessary, fundal pressure can be used to facilitate the birth of the anterior shoulder.

If the manoeuvre described is not successful, internal pressure against the presenting or rear scapula can be performed to adduct the shoulder and to bring it into the diagonal position.

Procedure

- Use two fingers to feel along the supine side of the foetus for the most accessible shoulder.

- Exert considerable pressure on the scapula so that this is adducted towards the child’s chest and the shoulder is brought into the diagonal position with respect to the mother’s pelvis (Rubin’s manoeuvre). With adduction, the biacromial diameter is reduced.

If this manoeuvre is not successful:

- Hook two fingers under the posterior armpit and rotate by 180° in the direction of the child’s back (Woods’ manoeuvre) or in the direction of the abdomen. The woman is only allowed to push once this manoeuvre is underway. The head should be flexed sacrally when the shoulder approaches the pubic symphysis so that this can pass under the pubic symphysis. If this does not work either, an attempt can be made to remove the posterior arm.

- Insert two fingers of the hand corresponding to the foetal shoulder and follow the upper arm on the rear side to the elbow.

- Splint the upper arm with one finger, and flex the forearm with the other finger. Subsequently, ‘sweep’ the entire arm over the ventral side of the child towards the outside. If the forearm is completely stretched, this will be difficult, or even impossible, and the effort should be aborted.

- If this is possible, the hand should be taken and carefully pulled out. Fracturing of the humerus can easily occur during this procedure. After the posterior arm has been born, the anterior shoulder can be delivered. If this does not succeed, the anterior shoulder should be rotated backwards and the arm will be born in the same manner. An effort can also be made to deliver the anterior arm immediately.

- Insert two fingers into the vagina along the supine side of the child.

- Hook one finger under the axilla of the anterior shoulder.

- Splint the upper arm with the other finger.

- Exert traction on the anterior shoulder, if necessary, in combination with external pressure.

- Bring the anterior arm out in a sweeping motion across the child’s face.

If all of the previous measures fail, the Zavanelli manoeuvre is also described. This process consists of turning back the external rotation, flexing the head and using continuous moderate pressure with a full hand to push the head back as far as possible into to the birth canal. For this to succeed, the head must remain well flexed. In effect, the birth of the head is turned back in reverse order. After that, the child should be born by means of a caesarean section. The uterus can be relaxed by administering a bolus injection of a beta-sympathicomimetic, an oxytocin antagonist (Atosiban), or halothane anaesthesia.